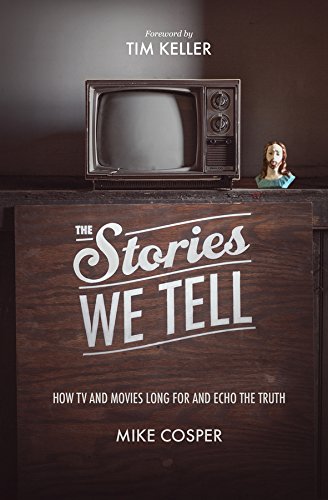

Review: Mike Cosper’s The Stories We Tell

Some Christians are allergic to the surrounding culture whether that’s books or tv’s or movies. Before Mike Cosper submerges the reader into the pursuit of understanding these cultural artifacts, in the Foreword Tim Keller says,

[In] the end, learning this discipline—of seeing God’s story in the stories we tell today—will be a way for us to deepen our own understanding of and joy in the gospel we believe. (12)

That’s what most Christians must understand before they might be willing to give this kind of cultural handiwork a fair hearing. Knowing the cultural stories you are already submerged in assists in seeing God’s story with clarity. Cosper calls stories “a great gift from a great storytelling God” (25 also see 216)—and he’s right. That’s the heart of what Cosper is striving for and what he achieves.

To understanding what Cosper gets at and to know if he’s achieved this end, we must look at an underlying premise. I’ve reviewed James K. A. Smith’s liturgy series books Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom. Cosper takes Smith’s argument and applies it to the stories he examines. He calls these stories “evidence of longing and desire” (38). The gist is that the stories we tell and hear strike at our heart. They speak to what we love and habituate us to love aright. That’s part of the importance of storytelling. This power to train and move our affections. Cosper says,

So what happens, then, in a world full of image-bearing storytellers who simultaneously long for redemption and hide from it? They tell other stories. Lots of them. (31)

Cosper takes the popular approach when framing the stories he considers—creation, fall, redemption, consummation (212, 216). He highlights these biblical narrative markers both positively and negatively. His analysis were careful and winsome. The Stories We Tell encourages sharp, critical, and biblical thinking—things sorely absent from a lot of cultural analysis.

I also appreciate the way Mike pushed back at the kind of cultural analysis that is more interested in ghost hunting for the sake justifying rotten cultural fruit. “Piling Christian language and ideas on top of dehumanizing entertainment . . . isn’t a successful exercise in redeeming culture” (41). Mike tackles this pastoral as well. He shares a story about a guy he’s counseling who’s struggling with lust and after their counseling session asks Mike if he will see a movie with some sexual content. Mike’s response was perfect. He was astonished that after describing his struggle with lust he was so quickly disconnected from that reality when discussing his entertainment choices.

My favorites chapters dealt with the fall. It’s often more difficult for Christians to think well through fall stories in my experience. He performs gut surgery on Mad Men and The Wire. Mad Men is the story of Don Draper’s fall. I’ve followed this show on tv and he helped me see things I’ve missed in this story. The Wire I’ve never watched, but it’s on my short list now. I won’t give away too much as far as his analysis goes, but he does an end one of the fall chapters with a comment I would like to share. “Fall stories orient us to a world that doesn’t work out how we expect. They help us make sense of the ruin we see around us. They help us know we’re not alone in our sorrows and failures, and they point to the deep need we all have for answers, for hope, and for redemption” (114). That’s why we need fall stories. If every story we watched/heard was a happily ever after we would not be prepared for the actual world we inhabit.

At one point in discussing our longing for Eden, Mike remarks “We make weak gods, and our stories reveal that we’re already aware of that fact” (75). That made me think of Joss Whedeon’s Avengers and Hulk slamming Loki side to side like a rag doll. Hulk says, “Puny god.” And isn’t that true? Even our best attempts to create a world where gods exist and they are puny. Our favorite Asgardian heroes have major flaws. Heck, all superheroes have issues. Tony Stark has an ego. Spiderman is insecure and afraid to love. Batman is depressed. Mr. Incredible adds 40 pounds, is out of shape, and searching for meaning out of the costume. We make weak gods.

Ultimately, we need more storytellers. We need more beauty. We need what The Stories We Tell offers. “Storytellers are probing at how we got into this mess of a world, noticing the wonders it contains, and imagining the possibilities that might make the world better, or might make us paper in the midst of it” (215). Keller began by talking about learning the discipline of seeing God’s story in other stories to know God. If knowing God is our chief end; if training our affections to love Him matures our faith—then stories should be a crucial part of Christian formation. To this end, Mike Cosper’s work in The Stories We Tell is invaluable.

Mathew B. Sims is the author of A Household Gospel: Fulfilling the Great Commission in Our Homes and a contributor in Make, Mature, Multiply (GCD Books). He completed over forty hours of seminary work at Geneva Reformed Seminary. He also works as the managing editor at Gospel-Centered Discipleship and the assistant editor at CBMW Men’s Channel. He regularly writes for a variety of publications. Mathew offers freelance editing and book formatting. He is a member at Downtown Presbyterian Church in Greenville, SC.

Useful resources

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Online Migliori

- Casino Italiani Non Aams

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- ξενες στοιχηματικες εταιριες

- Best Online Casino Canada

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Beste Online Casino Nederland

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne France

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Non Aams

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Aams Casino

- Meilleur Site De Casino En Ligne Belgique

- Casino En Ligne

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne En Belgique

- Siti Scommesse Non Aams Affidabile

- Lista Casino Online Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne

- Paris Sportif Mma Ufc

- Bookmaker Hockey Hors Arjel

- オンラインカジノ 出金 早い

- 仮想通貨カジノ

- Casino En Ligne 2026

- Casino Senza Verifica

- Crypto Casino

- Casino En Ligne Français