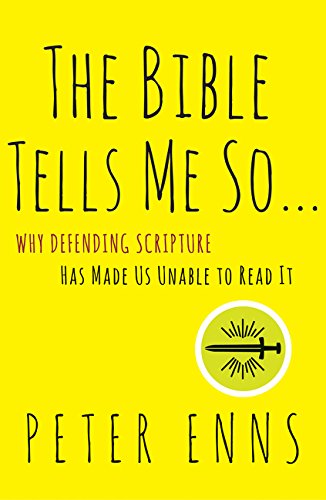

Review: Peter Enns’ The Bible Tells Me So

“Christians, don’t expect more from the Bible than you would of Jesus” (243).

Peter Enns is a familiar name in the discussion on the content and purpose of the Christian Scriptures. In The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It, Enns brings a wealth of humor and honest questions to many common held beliefs among conservative Christians. The jokes range in value. The questions are necessary. Enns’ answers are the source of controversy and disagreement.

Enns starts The Bible Tells Me So with a flurry of helpful statements and personal history (chapter 1). Enns’ story acts as background for his thesis that conservative Christians demand too much of the Bible. One cannot disagree with the statement “the Bible isn’t the problem” (7-9) since the church must reform itself to the Scriptures. Disagreements occur over what the Scriptures are ontologically and what they were written to communicate. This reflects itself in many head nods to Enns’ thorough questions only to respond to his answers with head shakes. Ultimately though the church needs “to learn that trusting God is not the same thing as trusting the Bible” (21). While some conservatives many be unwilling to affirm this, it remains common ground to share with Enns.

The major element of The Bible Tells Me So is Enns’ approach to human authors writing in their specific time and context. In particular Enns ties together the fundamental ideals of the incarnation (e.g. Jesus Christ as fully God and fully human) and brings them to the Scriptures. In his criticism of conservative approaches to the Bible, Enns puts forth this incarnational view of the Scriptures that attempts to take the human authors and their situations seriously. Enns provides examples of differing viewpoints on history in Joshua/Judges (36-40) and the Gospels (78-81). The concept of history or remembering as “interpretation” and not just recounting facts (75) is valuable but often falls short of showing the blatant contradiction Enns believes exists. This is particularly true when Enns discusses the law of Israel (160-164). Though there are valuable questions (e.g. how to harmonize Lev 15:24 and Lev 20:18) it seems pertinent to ask why Enns is so focused on the “story” of the Bible, yet fails to provide pressing questions about the change in law in the desert and the Promised Land. It is ironic that for material focused on presenting the growth and development of Israel’s story, most of the “contradictions” put forth are displayed as if on stage together against the same backdrop. Enns seems guilty of the very practice he challenges.

These types of over-exaggerations unfortunately derail many excellent points and valuable questions for conservative Christians. Throughout “Why Doesn’t God Make Up His Mind” (chapter 4) Enns repeatedly challenges the concept that the Bible can simply be read as a rulebook or “step-by-step instructional guide” (136). There is a strong element of truth to the thesis, but establishing this from the Old Testament’s wisdom literature (e.g. Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Job; 137-149) is rather poor. Many of Enns’ ideas are adequately reflected in these passages, but hardly warrant universal application to the entirety of the Scriptures. Once again, Enns sets the “story” against a pale and uniform backdrop that does a serious disservice to the distinct genres of the Scriptures.

In the end, Enns’ view of the Bible is starkly familiar to the allegorical interpretations of the early Alexandrian school. The emphasis of the Scriptures is on the spiritual aspects (presented wonderfully in chapter 3) and reading Jesus into the Bible (201-205) while making light of factual history (again chapter 3). This result is an approach that is historically “Christian” (Enns does affirm the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ) but goes against the grain of the current conservative consensus. The Bible Tells Me So is a valuable example of hermeneutical criticism with an equally faulty hermeneutic. Enns, alongside the conservative Christians who refuse to commune with him, remains a puzzling example of enlightenment thinking that continues to tell people what the Bible must say and do.

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received this book free from the publisher. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.”

Joshua Torrey is a New Mexico boy in an Austin, TX world. He is husband to Alaina and father to Kenzie & Judah and spends his free time studying for the edification of his household. These studies include the intricacies of hockey, football, curling, beer, and theology. You can follow him @AustinPreterism and read his theological musings and running commentary of the Scriptures at The Torrey Gazette.